Frederick Web Technology WebAudio Talk

Jan 04, 2024Introduction

This post contains my notes for my upcoming (at the time of writing) talk for the Frederick Web Technology meetup! The goal of this post (and the talk) is give a brief overview of what WebAudio is, what it can do, and how to use it. What you may be reading might not be done! Caveat Emptor!

Also, here’s a link to the demo page.

What is WebAudio

WebAudio is:

- A built-in API in the browser

- That allows programmatic access to play and control audio

- Via a “node-based” interface (not NodeJS!)

It supports lots of different workflows and features, such as:

- Loading and decoding an audio file for playback

- Playing a buffer of audio data (presumably loaded from a file, but maybe synthesized?!)

- Applying effects to audio in real-time

- Synthesizing audio with some basic oscillators

Stepping Back: How Does Digital Audio Even Work?

What is Sound?

- Sound is basically “wiggly air”

- Something moving in air fast enough causes the air to compress and expand which our ear drums detect by sympathetic vibration

- Our auditory nerve converts this to an electral signal which our brain perceives as sound.

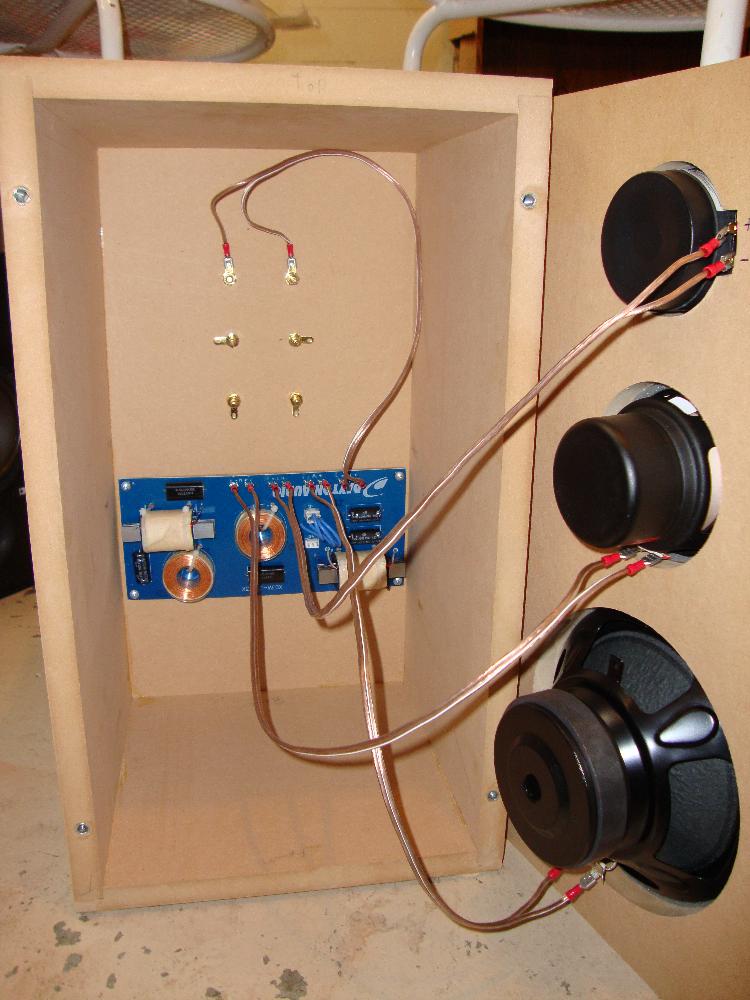

Speakers

The overly simplified version:

- Speakers work backwards than our ears

- A voltage is applied across an electromagnet

- Changes in the voltage cause the magnet to move a “cone” forward and backwards, causing air to be compressed and expanded.

- Our ears pick up the compressed and expanded air as sound.

How Computers Play Sound: Bitstreams, PCM, Bit Depth, Sample rate

To play a sound, the computer reads a bitstream, basically a stream of integers, and converts that to an output voltage to the speakers. Assuming it’s a signed integer, a negative number corresponds to a negative voltage, and a positive number corresponds to a postive voltage. As the computer loops over the numbers, the speaker moves back and forth generating sound. So, in essence an audio file (or stream) is a long array of integers with “speaker displacement” values. This is referred to as PCM encoding and is more-or-less how a WAV file works. The size of the integer (8-bit, 16-bit, etc) is the bit depth, and the number of integer values to loop over per second is called the sample rate (it’s typically 44.1 KHz).

Other Encodings

Some napkin math would quickly reveal that raw 16-bit PCM data at 44.1 KHz takes up a lot of space (~5MB a minute). So, engineers have come up with compression algorithms to improve that performance. Some are lossy like MP3, and some are lossless like FLAC.

In order to play these types of files they’d need to be decoded to PCM first. Many decoders can do this on-the-fly (like the <audio/> tag)!

How Does WebAudio Approach Sound In General?

- All WebAudio access occurs through an

AudioContextobject. - Audio data flows through a “node graph”, where each node adds audio, or modifies the signal.

For instance, you may load an audio file into an

AudioBufferSourceNode, then .connect() that a GainNode to control the volume, the .connect() the gain node to the AudioContext’s destination which allows the sound to play.

Some Nodes have parameters (AudioParam) associated with them.

For instance, a GainNode has a gain parameter that you can set to control the volume.

Moreover, you can connect some nodes to parameters.

For instance, you could connect an OscillatorNode a gain parameter which would make the volume change over time.

Our First WebAudio Page: Playing a sound file

// For UX reasons, most browsers don't allow audio playback until the initial

// page interaction. In general, you'd put this inside of a document click

// event of some sort

const context = new AudioContext();

// load and decode

const response = await fetch("never_gonna_give_u_up.mp3");

const buffer = await response.arrayBuffer();

const pcmData = await context.decodeAudioData(buffer);

// create a node for playing the buffer and connect to the speakers/destination

const bufferSource = await context.createBufferSource();

bufferSource.buffer = pcmData;

bufferSource.connect(context.destination);

bufferSource.loop = true;

bufferSource.start();

// "We're no strangers to love..."

A Minor Refactor For Ease of Use

We’re going to make a little function to make this easier for some later things…

async function loadPCMData(context, path) {

const buffer = await fetch(path);

const pcmData = await context.decodeAudioData(buffer);

return pcmData;

}

const context = new AudioContext();

const bufferSource = await context.createBufferSource();

bufferSource.buffer = await loadFile("never_gonna_give_u_up.mp3");

bufferSource.connect(context.destination);

bufferSource.loop = true;

bufferSource.start();

Going Further: Adding Effects

Let’s expore some other nodes that are available to us. We’ll keep our existing setup, but remove this line:

// Goodbye!

bufferSource.connect(context.destination)

We’re going to try shimmying in other nodes to see what they do!

BiquadFilterNode

Fancy name, but this node allows us to cut out high or low frequencies. This is sometimes referred to as a “high-pass”, “low-pass”, or “band-pass” filter because it allows high, low, or a band of frequencies to “pass through” the filter while other frequencies are cut out.

bufferSource.buffer = pcmData;

const filter = context.createBiquadFilterNode({

type: "lowpass", // "highpass" is also supported + many others!

frequency: 200, // the frequency in Hz to begin frequency cut-off

Q: 1, // how sharp the frequency fall-off is

})

bufferSource.connect(filter);

filter.connect(context.destination);

bufferSource.loop = true;

ConvolverNode

A ConvolverNode sounds fancy, and is! It convolves a source sound file with another creating a new audio stream.

For our purposes, you can convolve a audio source against an “impulse response” audio file which will allow us to emulate reverb!

Here’s how you’d do that:

const reverb = await context.createConvolver();

reverb.buffer = await loadFile("impulse_response.mp3");

bufferSource.connect(reverb);

reverb.connect(destination);

WaveShaperNode

A WaveShaperNode has the ability to take an input signal and map it to a new volume based on the volume of the input. Think of it as a function:

A couple of useful applications of this might be to:

- Add fuzz or distortion to a signal

- Implement a “gate” that doesn’t allow signals below a certain threshold through

Let’s implement a simple distortion:

const SAMPLES = 44100;

const curve = new Float32Array(SAMPLES);

const max_volume = 0.5;

const distortion_amount = 2.0

for (let i = 0; i < SAMPLES; i++) {

const x = (i * 2) / (SAMPLES - 1);

curve[i] = Math.sign(x) * distortion_amount * Math.pow(Math.abs(x), distortion_amount)

}

const distortion = await context.createWaveShaper();

distortion.curve = curve;

distortion.oversample = "4x"; // prevents some aliasing in the output signal

bufferSource.connect(distortion);

distortion.connect(context.destination);

Getting Lower-Level: Oscillators

WebAudio also gives us the ability to synthesize audio ourselves.

The most simplistic way to do this is to use an OscillatorNode.

An OscillatorNode is very simple: it generates a simple audio signal, like a sine or sawtooth wave, at a specified frequency. Here’s how you’d set it up:

const osc = new OscillatorNode(context, {

frequency: 220, // A below middle C

type: "sine", // square, sawtooth, triangle, and custom are supported

});

const volume = new GainNode(context, {

gain: 0.1, // oscillators are kinda loud...

})

osc.connect(volume);

volume.connect(context.destination);

// Don't forget this part! (I always do...)

osc.start();

What’s This “custom” Type All About?

OscillatorNodes allow you to also set your own waveform, instead of the built-in ones like sine, sawtooth, and triangle. This is achieved by calling osc.setPeriodicWave. Here’s a basic setup:

const real = new Float32Array(2);

const imag = new Float32Array(2);

real[0] = 0;

imag[0] = 0;

real[1] = 1;

imag[1] = 0;

const wave = context.createPeriodicWave(real, imag);

osc.setPeriodicWave(wave);

But… What do we set real and imag to? To figure this out, we’d have to take our waveform want and manually calculate the Fourier Series. The Fourier Series is a way of representing a oscillatory signal in terms of it’s constituent frequencies. This requires some non-trivial calculus so it’s perhaps not for the faint of heart…

However, here’s an example where I set an oscillator’s periodic wave to emulate a PWM waveform with configurable duty cycle (like the old NES pulse wave channels had!).

Ultimate Control: Audio Worklets

I suspect I won’t have time to cover this so I’m going to provide a link instead and provide a brief overview.

An AudioWorklet allows you to have full programmatic control over how a signal is manipulated at a “per-block” (read per chunk of audio samples) level. They run on a separate thread for performance purposes and are intended to replace the old ScriptProcessorNode which has been deprecated.